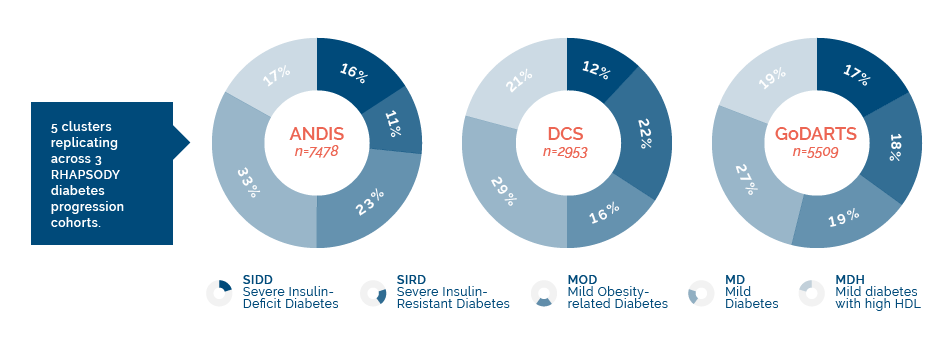

Three large human cohorts of diabetes progression, where patients have been diagnosed with type 2 diabetes and where the progression of disease in each individual is followed over time, have been extensively studied. As an early RHAPSODY finding, we identified a new way to classify type 2 diabetic patients into 5 different ‘clusters’. Each ‘cluster’ has very specific characteristics and its own unique risk of diabetic complications. If an individual displays certain characteristics then he/she belongs to one of these five clusters.

In addition, RHAPSODY scientists have defined “molecular signatures” of these five clusters by investigating biomarkers specific to each cluster.

What are the omics?

Multi-omics refer to biological information in the form of any molecules in our bodies which are part of our everyday functioning and can change in the course of diseases. By measuring the omics, we can put together millions of small pieces of information to understand diseases at an information-rich and complex level. Multi-omics integrate various data sets of different -omic groups, including genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics and metabolomics.

How to measure the omics?

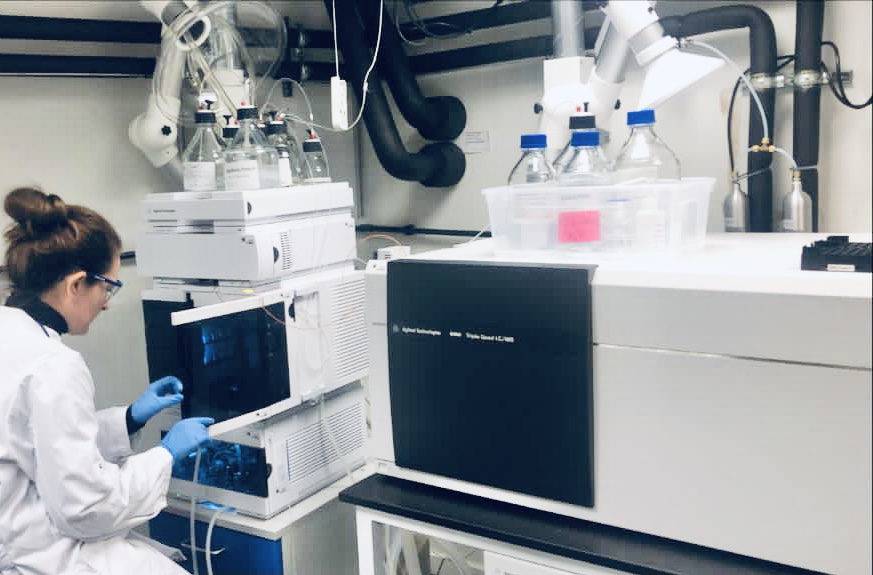

To measure the omics we use state of the art technology. Since this is a new field, it requires the knowledge of many specialists, from engineers to big data scientists. The machines and methods to acquire and understand the data are developed by scientists in research centres. For each omic there are many methods and degrees of detail one can measure. Here in the picture the Steno Diabetes Center platform was used for the targeted metabolomics analyses of blood samples from 6,000 patients with diabetes. This has enabled us to acquire accurate data relating to small molecules that are important in diabetes, and we have already identified a number of promising candidate biomarkers of type 2 diabetes. We have also replicated these initial findings, using multi-omics data from two patient cohorts (ANDIS and ACCELERATE, learn more here).

What is “precision medicine”?

“Precision medicine” or “personalized medicine” attempts to take the differences in our omics or new molecular measurement into account, using individualized data to tailor customized treatment.

For example, novel biomarkers promise to help tailor and target early treatment specific to those patients who would benefit most.

What is the future of the novel biomarkers beyond RHAPSODY?

Molecular data can be complex. Fortunately, there are algorithms that can help us identify the relevant information for each individual.

Biomarkers may help identify patients who are more (or less) likely to progress from initial type 2 diabetes diagnosis to pancreatic failure and the need for insulin treatment. Statistical models to differentiate between “fast” and “slow” progressors include not only traditional information, i.e. clinical measures as well as patient medical history, but also newly identified biomarkers.

Such biomarkers could also be used in controlled clinical trials for a faster and more effective study conduct.

Clinical Data Interchange Standards Consortium. A set of widely used standards for clinical data.

A research study in which one or more human subjects are prospectively assigned to one or more interventions (which may include placebo or other control) to evaluate the effects of those interventions on health-related biomedical or behavioral outcomes (source: https://grants.nih.gov/).

Patient cohort: A group of individuals affected by common diseases, environmental or temporal influences, treatments, or other traits whose progress is assessed in a research study (source: https://medical-dictionary.thefreedictionary.com/)

Computer simulation models are a common tool to predict how different treatments may affect disease progression and outcomes. They are used to extrapolate the findings of clinical trials into lifetime costs and health benefits.

Diabetes is a chronic disease characterised by chronically elevated levels of blood sugar (hyperglycemia), due to alterations in the production or the use of insulin by the body. Insulin action is vital to ensure that glucose (sugar, basic source of energy) from our food is properly utilised by cells of the human body.

Insulin is a hormone produced by the pancreas (more precisely by pancreatic beta cells), which is crucial to control blood glucose (glycemia). Once secreted into the blood stream, insulin orchestrates a coordinated response to lower blood glucose by acting on several tissues (namely insulin-target tissues). Notably, insulin stimulates glucose uptake by muscle and fat (adipose tissue) and prevents glucose production by the liver.

For a long time, diabetes has been labelled either ‘type 1’ or ‘type 2’ diabetes. Type 2 diabetes is the result of failures across several complex biological systems. Compared to those with type 1 diabetes, patients with type 2 diabetes can still produce insulin, at least during the first stages of the disease (prediabetes and early type 2 diabetes). However, their insulin-target tissues stop responding to the normal amounts of insulin produced after eating: this so-called “insulin resistance” process prevents glucose uptake by cells, resulting in rise of blood glucose. Chronic hyperglycemia tricks the pancreas into over-producing insulin. If untreated, this vicious circle of events can spiral out of control leading to an exhaustion of the pancreas (“pancreatic beta cell failure”) to produce insulin (insulin deficiency).

Diabetes is a major public health problem since over time, it can damage heart and blood vessels (heart attacks and strokes), nerves (neuropathy resulting in foot ulcers and possibly limb amputation), eyes (retinopathy leading to blindness) and kidneys (nephropathy).

Epigenetics is the study of how behaviors and environment can cause changes that affect the way genes work. Unlike genetic changes, epigenetic changes are reversible and do not change DNA sequence, but they can change how the body reads a DNA sequence (source: https://www.cdc.gov/genomics/disease/epigenetics.htm).

Elovl2: this gene encodes for the protein called "Elongation of very long chain fatty acids protein 2" which catalyzes the first and rate-limiting reaction of the four reactions that constitute the long-chain fatty acids elongation cycle. This endoplasmic reticulum-bound enzymatic process allows the addition of 2 carbons to the chain of long- and very long-chain fatty acids (VLCFAs) per cycle (source: https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q9JLJ4)

A server containing a clinical database which can be connected to from a central computer using web services (HTTPS)

A surgical bypass operation that typically involves reducing the size of the stomach and reconnecting the smaller stomach to bypass the first portion of the small intestine so as to restrict food intake and reduce caloric absorption in cases of severe obesity (source: https://merriam-webster.com/).

Organs where insulin exerts its blood glucose lowering action. Liver: insulin decreases glucose production; muscles and adipose tissue: insulin stimulates glucose uptake.

Multi-omics refer to biological information in the form of any molecules in our bodies which are part of our everyday functioning and can change during diseases.

Genomics: study of the full genetics components of an organism (the genome) which includes the entire DNA sequence. It also considers the inter-relationships between the genes and their interaction with environmental factors.

Transcriptomics: transcriptomics is used to identify the qualitative and quantitative RNA levels in the whole genome. It can tell us which transcripts are present together with the levels of their expression. Almost 80% of the genome is transcribed to RNA.

Proteomics: study of the structure, function and physiological role of the entire proteins in a cell or tissue of an organism.

Metabolomics:study of the metabolites present in a cell or tissue/fluids of an organism. This includes small molecules, carbohydrates, peptides, lipids, nucleosides and metabolism products.

A set of concepts and categories in a subject area or domain that shows their properties and the relations between them.

A phenotypic trait is an obvious, observable, and measurable trait; it is the expression of genes in an observable way. An example of a phenotypic trait is a specific hair color. Underlying genes, which make up the genotype, determine the hair color, but the hair color observed is the phenotype. The phenotype is dependent on the genetic make-up of the organism, and also influenced by the environmental conditions (source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Phenotypic_trait)

PNLIPRP1: this gene encodes for the protein called "pancreatic lipase-related protein 1" which may function as inhibitor of dietary triglyceride digestion (source: https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/P54315)

Precision medicine refers to the tailoring of medical treatment to the individual characteristics of each patient, […] the ability to classify individuals into subpopulations that differ in their susceptibility to a particular disease, in the biology or prognosis of those diseases they may develop, or in their response to a specific treatment (definition from the US National Research Council, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Precision_medicine).

When fasting blood glucose is raised beyond normal levels, but is not high enough to warrant a diabetes diagnosis (source: https://diabetes.co.uk/)

Health benefits are often expressed as quality-adjusted life years (QALYs). QALYs combine longevity and quality of life in a single metric and allow comparisons across different treatments and diseases. As a result, the impact on QALYs are required by several European agencies to make decisions about whether to adopt and reimburse medicines at a national level.

A programming language and free software environment for statistical computing and graphics supported by the R Foundation for Statistical Computing. The R language is widely used among statisticians and data miners for developing statistical software and data analysis (source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/R_(programming_language)).

An integrated development environment for R that runs on Windows, Mac or Linux operating systems.

Sensitivity is the proportion of true-positives which actually test positive, and how well a test is able to detect positive individuals in a population (source: https://www.fws.gov/aah/PDF/SandS.pdf).

Specificity is the proportion of true-negatives which actually test negative, and reflects how well an assay performs in a group of disease negative individuals (source: https://www.fws.gov/aah/PDF/SandS.pdf).

This work has been supported by the Swiss State Secretariat for Education‚ Research and Innovation (SERI) under contract number 16.0097-2.

The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of these funding bodies.